The preface provides insight into the translators' work and vision, their aim to make God's Word accessible and their response to criticism. It highlights their dedication and the centrality of the Bible to faith. Reading the preface provides a deeper understanding of the historical and theological context behind this influential translation.

Expand the tab below to see this overview;

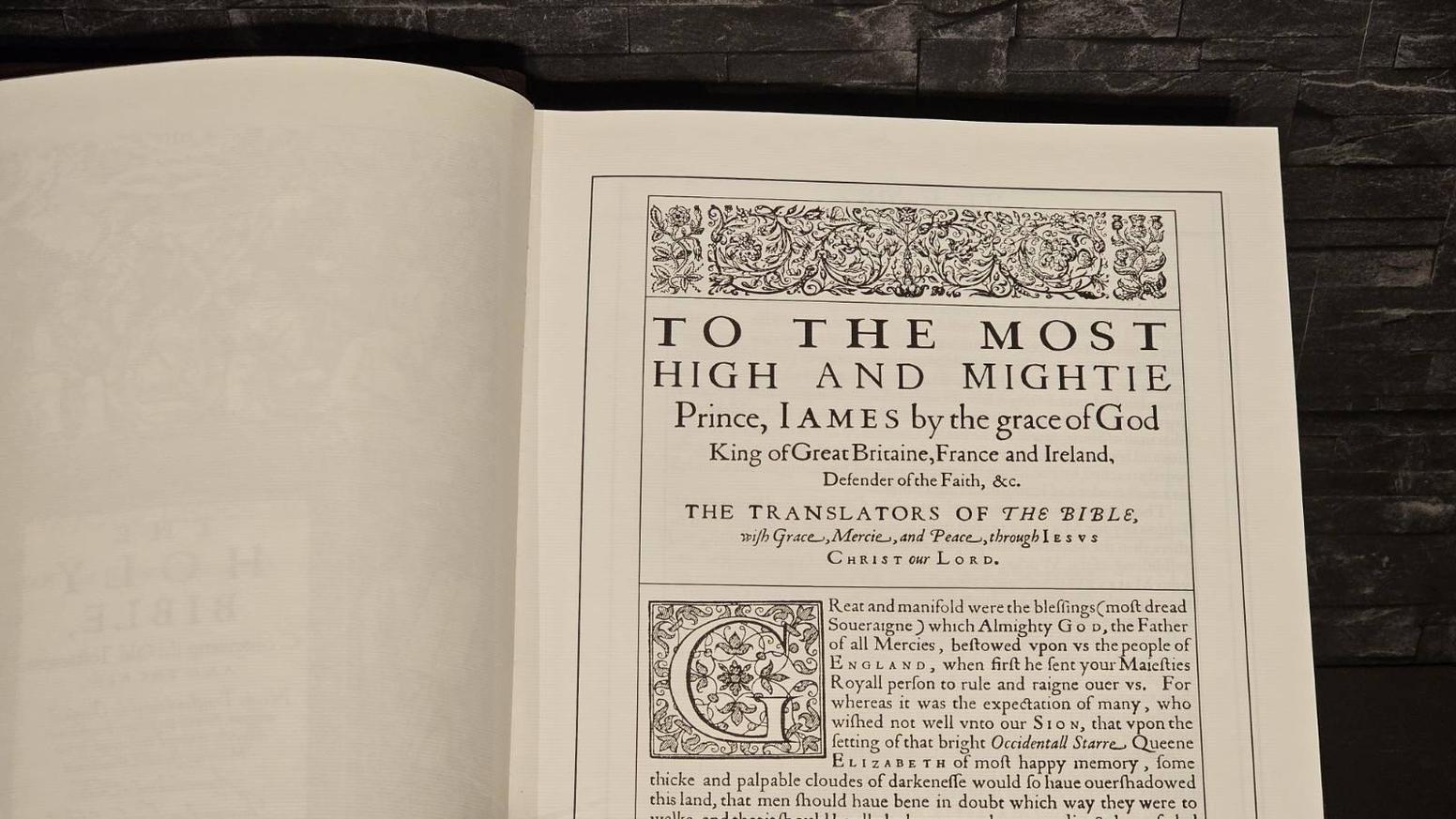

Overview of KJV 1611 Preface

Overview of the Preface to the 1611 King James Version

The Preface to the 1611 King James Bible is a rich and thought-provoking text that provides insight into the vision, work and theological convictions of the translators. It explains why the translation was made, its aim to make God's word accessible to more people, and their pursuit of accuracy and fidelity to the original texts. The preface also responds to criticisms from contemporary opponents and highlights the challenges that come with undertaking a work of such importance.

By reading the preface, one gains a deeper understanding of the translators' dedication, their view of the centrality of Scripture to faith, and the historical context that made this translation so influential. It is a powerful reminder of the importance of the Bible and the people who worked to bring it closer to the people.

This detailed overview offers an in-depth structure and a clear understanding of the various parts and themes covered in the preface to the 1611 King James Bible.

1. Introduction

Opening

The authors begin by explaining why they are writing the preface.

Emphasise the importance of spreading God's word in the English language.

2. Historical Context

Previous translations

Close description of previous translations and their contribution to the spread of the Bible.

Criticism and limitations of these previous translations.

The Need for a New Translation

Arguments that the English Bible needed a new and more accurate translation.

The need to reflect the evolution of the language and provide a clearer understanding of the scriptures.

3. Translation Process

Composition of the Committee

Description of the scholars involved in the translation, including their qualifications and expertise.

Structure and organisation of the translation work, including the different groups and their specific roles.

Methodology

Detailed description of the methods and principles used.

Emphasis on accuracy and a comparison of different manuscripts.

Use of previous translations as reference material.

Consultation with scholars from other countries and traditions to ensure the quality of the translation.

4. The Importance of the Bible

The Word of God

Emphasise the authority of the Bible as the Word of God.

Discuss the importance of having an accurate and understandable translation to understand God's will.

Spiritual Guidance

How the Bible serves as a source of moral and spiritual guidance.

Examples of how the Bible can influence individual lives and society at large.

5. Defense of the Translation

Criticism and Expectations

Responding to potential criticism of the translation.

Expectations of what the new translation should achieve.

Discussing possible mistakes and human limitations in the translation process.

Dedication of the translators

Presentation of the translators' dedication and accuracy in their work.

Use of many resources and expertise to ensure the quality of the translation.

6. Conclusion

The Prayer for Success

A prayer that the translation will be well received and beneficial to all believers.

Hope that the translation will lead to greater understanding and faith.

Gratitude

Expression of gratitude to all who have contributed to the project.

Recognising the support of church and secular leaders.

1611 PREFACE

Part 2

From the translators to the readers

The best things have been calumniated

This section discusses how even the most

valuable and well-intentioned acts often face criticism and opposition. The

translators recognise that their work may be attacked by both Catholics and

some Protestant groups, but they assure us that they have worked with integrity

and a sincere desire to serve God.

Zeal to promote the common good, whether it be by devising anything ourselves, or revising that which hath been laboured by others, deserveth certainly much respect and esteem, but yet findeth but cold entertainment in the world. It is welcomed with suspicion instead of love, and with emulation instead of thanks: and if there be any hole left for cavil to enter (and cavil, if it do not find a hole, will make one), it is sure to be misconstrued, and in danger to be condemned.

This will easily be granted by as many as know story, or have any experience. For, was there ever anything projected, that savoured any way of newness or renewing, but the same endured many a storm of gainsaying, or opposition? A man would think that civility, wholesome laws, learning and eloquence, synods, and church maintenance (that we speak of no more things of this kind) should be as safe as a sanctuary, and out of shot (ἐκτὸς βέλους, "exw belouV"), as they say, that no man would lift up the heel; no, nor dog move his tongue against the motioners of them.

For by the first, we are distinguished from brute beasts led with sensuality; by the second, we are bridled and restrained from outrageous behaviour, and from doing of injuries, whether by fraud or by violence; by the third, we are enabled to inform and reform others, by the light and feeling that we have attained unto ourselves; briefly, by the fourth being brought together to a parle face to face, we sooner compose our differences than by writings, which are endless; and lastly, that the church be sufficiently provided for, is so agreeable to good reason and conscience, that those mothers are holden to be less cruel, that kill their children as soon as they are born, than those nursing fathers and mothers (wheresoever they be) that withdraw from them who hang upon their breasts (and upon whose breasts again themselves do hang to receive the spiritual and sincere milk of the word) livelihood and support fit for their estates.

Thus it is apparent, that these things which we speak of, are of most necessary use, and therefore, that none, either without absurdity can speak against them, or without note of wickedness can spurn against them.

Yet for all that, the learned know that certain worthy men [Anacharsis with others] have been brought to untimely death for none other fault, but for seeking to reduce their countrymen to good order and discipline; and that in some commonweals [e.g. Locri] it was made a capital crime, once to motion the making of a new law for the abrogating of an old, though the same were most pernicious; and that certain [Cato the elder], which would be counted pillars of the state, and patterns of virtue and prudence, could not be brought for a long time to give way to good letters and refined speech, but bare themselves as averse from them, as from rocks or boxes of poison.*

And fourthly, that he was no babe, but a great clerk [Gregory the Divine], that gave forth (and in writing to remain to posterity) in passion peradventure, but yet he gave forth, that he had not seen any profit to come by any synod, or meeting of the clergy, but rather the contrary. And lastly, against church maintenance and allowance, in such sort, as the ambassadors and messengers of the great King of Kings should be furnished, it is not unknown what a fiction or fable (so it is esteemed, and for no better by the reporter himself [Nauclerus], though superstitious) was devised--namely, that at such a time as the professors and teachers of Christianity in the Church of Rome, then a true church, were liberally endowed, a voice forsooth was heard from heaven, saying, "Now is poison poured down into the church," etc.*

Thus not only as oft as we speak, as one saith, but also as oft as we do anything of note or consequence, we subject ourselves to everyone's censure, and happy is he that is least tossed upon tongues; for utterly to escape the snatch of them it is impossible. If any man conceit, that this is the lot and portion of the meaner sort only, and that princes are privileged by their high estate, he is deceived. "As the sword devoureth as well one as the other," as it is in Samuel [2 Sam. 11:25]; nay, as the great commander charged his soldiers in a certain battle, to strike at no part of the enemy, but at the face; and as the king of Syria commanded his chief captains to "fight neither with small nor great, save only against the king of Israel" [1 Ki. 22:31]; so it is too true, that Envy striketh most spitefully at the fairest, and at the chiefest.

David was a worthy prince, and no man to be compared to him for his first deeds, and yet for as worthy as act as ever he did (even for bringing back the Ark of God in solemnity), he was scorned and scoffed at by his own wife [2 Sam. 6:16]. Solomon was greater than David--though not in virtue, yet in power--and by his power and wisdom he built a temple to the LORD, such a one as was the glory of the land of Israel, and the wonder of the whole world. But was that his magnificence liked of by all? We doubt of it. Otherwise, why do they lay it in his son's dish, and call unto him for easing of the burden [σεισαχθείαν]: "Make," say they, "the grievous servitude of thy father, and his sore yoke, lighter"? [1 Ki. 12:4] Belike he had charged them with some levies, and troubled them with some carriages. Hereupon they raise up a tragedy, and wish in their heart the temple had never been built. So hard a thing it is to please all, even when we please God best, and do seek to approve ourselves to every one's conscience.

The highest personages have been calumniated

The translators show that even prominent leaders like

King David and Solomon faced criticism despite their great deeds. This is used

as a parallel to explain that even a sacred project like Bible translation can

be unfairly criticised. They ask for understanding and support for their work,

recognising that opposition often accompanies significant efforts.

If we will descend to later times, we shall find many the like examples of such kind, or rather unkind, acceptance. The first Roman emperor [C. Caesar, according to Plutarch] did never do a more pleasing deed to the learned, nor more profitable to posterity, for conserving the record of times in true supputation, than when he corrected the calendar and ordered the year according to the course of the sun; and yet this was imputed to him for novelty and arrogance, and procured to him great obloquy.

So the first christened emperor [Constantine] (at the leastwise, that openly professed the faith himself, and allowed others to do the like), for strengthening the empire at his great charges, and providing for the church as he did, got for his labour the name Pupillus, as who would say, a wasteful prince, that had need of a guardian or overseer [Aurel. Victor]. So the best christened emperor [Theodosius], for the love that he bare unto peace, thereby to enrich both himself and his subjects, and because he did not see war but find it, was judged to be no man at arms [Zosimus] (though indeed he excelled in feats of chivalry, and showed so much when he was provoked), and condemned for giving himself to his ease and to his pleasure.

To be short, the most learned emperor of former times [Justinian] (at the least, the greatest politician), what thanks had he for cutting off the superfluities of the laws, and digesting them into some order and method? This, that he hath been blotted by some to be an epitomist—that is, one that extinguished worthy whole volumes, to bring his abridgments into request. This is the measure that hath been rendered to excellent princes in former times, even, Cum bene facerent, male audire—"for their good deeds to be evil spoken of."

Neither is there any likelihood that envy and malignity died and were buried with the ancient. No, no, the reproof of Moses taketh hold of most ages: "You are risen up in your fathers' stead, an increase of sinful men" [Num. 32:14]. "What is that that hath been done? that which shall be done, and there is no new thing under the sun," saith the wise man [Eccl. 1:9]; and St. Stephen, "As your fathers did, so do you" [Acts 7:51].

His Majesty's constancy, notwithstanding calumniation, for the survey of the English translations

In this section, the translators highlight the role of

King James I as a driving force behind the translation of the Bible, despite

facing criticism and opposition. They emphasise his determination and wisdom in

recognising the need for a more accurate and reliable English-language Bible,

based on the original sacred texts and taking into account previous

translations.

This, and more to this purpose, His Majesty that now reigneth (and long, and long may he reign, and his offspring forever, "Himself and children, and children's children always" [Αὐτὸς, καὶ παῖδες, καὶ παίδων παντότε παῖδες]) knew full well, according to the singular wisdom given unto him by God, and the rare learning and experience that he hath attained unto; namely, that whosoever attempteth anything for the public (especially if it pertain to religion, and to the opening and clearing of the word of God), the same setteth himself upon a stage to be glouted upon by every evil eye; yea, he casteth himself headlong upon pikes, to be gored by every sharp tongue.

For he that meddleth with men's religion in any part, meddleth with their custom, nay, with their freehold; and though they find no content in that which they have, yet they cannot abide to hear of altering. Notwithstanding, his royal heart was not daunted or discouraged for this that colour, but stood resolute, "as a statue immovable, and an anvil not easy to be beaten into plates" [ὡς πέρ τις ἀνδρίας ἀπερίτρεπτος καὶ ἀκμὼν ἀνὴλάτος], as one [Suidas] saith.

He knew who had chosen him to be a soldier, or rather a captain, and being assured that the course which he intended made much for the glory of God, and the building up of his church, he would not suffer it to be broken off for whatsoever speeches or practices. It doth certainly belong unto kings, yea, it doth specially belong unto them, to have care of religion; yea, to know it aright; yea, to profess it zealously; yea, to promote it to the uttermost of their power. This is their glory before all nations which mean well, and this will bring unto them a far most excellent weight of glory in the day of the Lord Jesus.

For the Scripture saith not in vain, "Them that honor me, I will honor" [1 Sam. 2:30]; neither was it a vain word that Eusebius delivered long ago, that piety towards God [θεοσέβεια] was the weapon, and the only weapon, that both preserved Constantine's person, and avenged him of his enemies [Eusebius lib. 10 cap. 8].

The praise of the Holy Scriptures

The Bible is held up by the translators as

a priceless treasure, greater than all worldly riches, because it leads to

eternal bliss. It is described as the light in the darkness, the comfort in

difficulties, and the guide that leads man to righteousness and salvation. The

Scriptures are the direct revelation of God, eternal and indispensable to the

Christian faith, and their translation into English aims to make this

life-giving Word accessible to all.

But now, what piety without truth? What truth (what saving truth) without the word of God? What word of God (whereof we may be sure) without the Scripture? The Scriptures we are commanded to search (John 5:39, Isa. 8:20). They are commended to those that searched and studied them (Acts 17:11; 8:28–29). They are reproved to those that were unskillful in them, or slow to believe them (Matt. 22:29; Luke 24:25). They can make us wise unto salvation (2 Tim. 3:15). If we be ignorant, they will instruct us; if out of the way, they will bring us home; if out of order, they will reform us; if in heaviness, comfort us; if dull, quicken us; if cold, inflame us.

"Tolle, lege; tolle, lege" ("Take up and read, take up and read") the Scriptures. For unto them was the direction, it was said unto St. Augustine by a supernatural voice [S. August. Confess., lib. 8, cap. 12]. “Whatsoever is in the Scriptures, believe me,” saith the same St. Augustine, “is high and divine; there is verily truth, and a doctrine most fit for the refreshing of men’s minds, and truly so tempered, that everyone may draw from thence that which is sufficient for him, if he come to draw with a devout and pious mind, as true religion requireth” [S. August. De Utilit. Credendi, cap. 6].

Thus St. Augustine. And St. Jerome: Ama scripturas, et amabit te sapientia [S. Hieronym. Ad Demetriad.], "Love the Scriptures, and wisdom will love thee." And St. Cyril against Julian: “Even boys that are bred up in the Scriptures, become most religious, etc.” [S. Cyril. Contra Julianum, lib. 7].

But why mention only three or four uses of the Scriptures, when whatsoever is to be believed, practiced, or hoped for, is contained in them? Why only three or four sentences of the Fathers, when whosoever is worthy the name of a Father, from Christ’s time onward, hath likewise written not only of the riches but also of the perfection of the Scripture? “I adore the fulness of the Scripture,” saith Tertullian against Hermogenes [Tertul. Adversus Hermogenem]. And again, to Apelles, a heretic of the like stamp, he saith, “I do not admit that which thou bringest in (or concludest) of thine own (head or store, de tuo) without Scripture” [Tertul. De Carne Christi].

So St. Justin Martyr before him: “We must know by all means,” saith he, “that it is not lawful (or possible) to learn (anything) of God or of right piety, save only out of the prophets, who teach us by divine inspiration” [Justin, Protrepticus]. So Saint Basil after Tertullian: “It is a manifest falling away from the faith, and a fault of presumption, either to reject any of those things that are written, or to bring in (upon the head of them, ἐπεισάγειν) any of those things that are not written” [S. Basil, Περὶ Πίστεως, ὑπερηφανίας κατηγορία].

We omit to cite to the same effect, St. Cyril, Bishop of Jerusalem, in his Fourth Catechesis, St. Jerome against Helvidius, St. Augustine in his third book against the letters of Petilian, and in very many other places of his works. We also forebear to descend to later Fathers, because we will not weary the reader.

The Scriptures, then, being acknowledged to be so full and so perfect, how can we excuse ourselves of negligence if we do not study them? Of curiosity if we be not content with them?

Men talk much of εἰρεσιώνη ("Εἰρεσιώνη σύκα φέρει, καὶ πίονας ἄρτους, καὶ μέλι ἐν κοτύλῃ, καὶ ἔλαιον", etc.), an olive bough wrapped about with wood, whereupon did hang figs, bread, honey in a pot, and oil—how many sweet and goodly things it had hanging on it; of the Philosopher’s Stone, that it turneth copper into gold; of cornucopia, that it had all things necessary for food in it; of Panaces, the herb, that it was good for diseases; of Catholicon, the drug, that it is in stead of all purges; of Vulcan’s armor, that it was an armor of proof against all thrusts and all blows, etc. Well, that which they falsely or vainly attributed to these things for bodily good, we may justly and with full measure ascribe unto the Scripture for spiritual.*

It is not only an armor but also a whole armory of weapons, both offensive and defensive, whereby we may save ourselves and put the enemy to flight. It is not an herb, but a tree, or rather a whole paradise of trees of life, which bring forth fruit every month, and the fruit thereof is for meat, and the leaves for medicine. It is not a pot of manna or a cruse of oil, which were for memory only, or for a meal’s meat or two, but as it were a shower of heavenly bread sufficient for a whole host, be it never so great; and as it were a whole cellar full of oil vessels; whereby all our necessities may be provided for, and our debts discharged.

In a word, it is a panary of wholesome food against finewed traditions; a physician’s shop (as St. Basil calleth it) [S. Basil, In Psalmum Primum] of preservatives against poisoned heresies; a pandect of profitable laws against rebellious spirits; a treasury of most costly jewels against beggarly rudiments; finally, a fountain of most pure water springing up unto everlasting life.

And what marvel? The original thereof being from heaven, not from earth; the Author being God, not man; the Inditer, the Holy Spirit, not the wit of the apostles or prophets; the penmen such as were sanctified from the womb, and endued with a principal portion of God’s Spirit; the matter, verity, piety, purity, uprightness; the form, God’s word, God’s testimony, God’s oracles, the word of truth, the word of salvation, etc.; the effects, light of understanding, stability of persuasion, repentance from dead works, newness of life, holiness, peace, joy in the Holy Ghost; lastly, the end and reward of the study thereof, fellowship with the saints, participation of the heavenly nature, fruition of an inheritance immortal, undefiled, and that never shall fade away.

Happy is the man that delighteth in the Scripture, and thrice happy that meditateth in it day and night.

Translation necessary

The

translators emphasise the importance of making the Bible available in English,

as it is impossible for people to meditate on or understand what they cannot

read in their own language. They argue that without translation, the Word of

God remains hidden and unusable to the majority, like a closed book or a source

without access. Therefore, translation is a necessity to spread God's truth to

all people.

But how shall men meditate in that which they cannot understand? How shall they understand that which is kept close in an unknown tongue? As it is written, "Except I know the power of the voice, I shall be to him that speaketh a barbarian, and he that speaketh shall be a barbarian to me" [1 Cor. 14:11]. The apostle excepteth no tongue; not Hebrew the ancientest, not Greek the most copious, not Latin the finest. Nature taught a natural man to confess that all of us in those tongues which we do not understand are plainly deaf; we may turn the deaf ear unto them.

The Scythian counted the Athenian, whom he did not understand, barbarous [Clem. Alex. Stromata, lib. 1]; so the Roman did the Syrian and the Jew (even St. Jerome himself called the Hebrew tongue barbarous, belike because it was strange to so many) [S. Hieronym. Ad Damasum]; so the Emperor of Constantinople [Michael, son of Theophilus] calleth the Latin tongue barbarous, though Pope Nicolas do storm at it [2 Tom. Concil., ex edit. Petri Crab.]; so the Jews long before Christ called all other nations Lognazim, which is little better than barbarous.

Therefore, as one complaineth that always in the senate of Rome there was one or other that called for an interpreter [Cicero, De Finibus, lib. 5], so, lest the church be driven to the like exigent, it is necessary to have translations in a readiness.

Translation it is that openeth the window, to let in the light; that breaketh the shell, that we may eat the kernel; that putteth aside the curtain, that we may look into the most holy place; that removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water, even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered [Gen. 29:10].

Indeed, without translation into the vulgar tongue, the unlearned are but like children at Jacob's well (which was deep) [John 4:11] without a bucket or something to draw with; or as that person mentioned by Isaiah, to whom when a sealed book was delivered, with this motion, "Read this, I pray thee," he was fain to make this answer: "I cannot, for it is sealed" [Isa. 29:11].

The translation of the Old Testament out of the Hebrew into Greek

The

Seventy Interpreters' Translation (often called the Septuagint) refers to the

Greek translation of the Old Testament, The name “Septuagint” comes from the

Latin word for “seventy” and reflects the legend that the work was done by 70

people in 70 days by Jewish scholars in Alexandria, Egypt. The KJV translators

refer to the fact that this translation was not complete and perfect, but that

it needed to be corrected in many places and that the translators of the

Septuagint have been noted adding to the original, and sometimes taking away

from it, but it contributed to the spread of God's word throughout the world.

While God would be known only in Jacob, and have His name great in Israel, and in none other place; while the dew lay on Gideon's fleece only, and all the earth besides was dry; then for one and the same people, which spake all of them the language of Canaan—that is, Hebrew—one and the same original in Hebrew was sufficient [S. August. lib. 12 contra Faust., c. 32].

But when the fulness of time drew near that the Sun of righteousness, the Son of God, should come into the world, whom God ordained to be a reconciliation through faith in His blood, not of the Jew only, but also of the Greek, yea, of all them that were scattered abroad; then lo, it pleased the Lord to stir up the spirit of a Greek prince (Greek for descent and language), even of Ptolemy Philadelph, king of Egypt, to procure the translating of the book of God out of Hebrew into Greek.*

This is the translation of the Seventy Interpreters, commonly so called, which prepared the way for our Saviour among the Gentiles by written preaching, as St. John Baptist did among the Jews by vocal. For the Grecians, being desirous of learning, were not wont to suffer books of worth to lie mouldering in kings' libraries, but had many of their servants, ready scribes, to copy them out, and so they were dispersed and made common.

Again, the Greek tongue was well known and made familiar to most inhabitants in Asia, by reason of the conquest that there the Grecians had made, as also by the Colonies which thither they had sent. For the same causes also it was well understood in many places of Europe, yea, and of Africa too. Therefore, the word of God, being set forth in Greek, becometh hereby like a candle set upon a candlestick, which giveth light to all that are in the house; or like a proclamation sounded forth in the marketplace, which most men presently take knowledge of; and therefore that language was fittest to contain the Scriptures, both for the first preachers of the gospel to appeal unto for witness, and for the learners also of those times to make search and trial by.

It is certain that that translation was not so sound and so perfect, but it needed in many places correction; and who had been so sufficient for this work as the apostles or apostolic men? Yet it seemed good to the Holy Ghost and to them, to take that which they found (the same being for the greatest part true and sufficient), rather than making a new, in that new world and green age of the church—to expose themselves to many exceptions and cavillations, as though they made a translation to serve their own turn, and therefore bearing a witness to themselves, their witness not to be regarded.

This may be supposed to be some cause why the translation of the Seventy was allowed to pass for current. Notwithstanding, though it was commended generally, yet it did not fully content the learned—no, not of the Jews. For not long after Christ, Aquila fell in hand with a new translation, and after him Theodotion, and after him Symmachus; yea, there was a fifth and a sixth edition, the authors whereof were not known. These with the Seventy made up the Hexapla and were worthily and to great purpose compiled together by Origen.

Howbeit, the edition of the Seventy went away with the credit, and therefore not only was placed in the midst by Origen (for the worth and excellency thereof above the rest, as Epiphanius gathereth [Epiphan. de mensur. et ponderibus.]), but also was used by the Greek Fathers for the ground and foundation of their commentaries. Yea, Epiphanius above-named doth attribute so much unto it, that he holdeth the authors thereof not only for interpreters, but also for prophets in some respect; and Justinian the Emperor, enjoining the Jews his subjects to use specially the translation of the Seventy, rendereth this reason thereof: because they were as it were enlightened with prophetical grace [S. August. 2o de doctrin. Christian. c. 15o. Novell. diatax. 146].

Yet for all that, as the Egyptians are said of the prophet to be men and not God, and their horses flesh and not spirit [προφητικὴς ὡςπερ χάριτος περιλαμβύσας αὐτοὺς, Isa. 31:3]; so it is evident (and St. Jerome affirmeth as much) [S. Hieron. de optimo genere interpret.] that the Seventy were interpreters; they were not prophets. They did many things well, as learned men; but yet as men they stumbled and fell, one while through oversight, another while through ignorance; yea, sometimes they may be noted to add to the original, and sometimes to take from it, which made the apostles to leave them many times, when they left the Hebrew, and to deliver the sense thereof according to the truth of the word, as the Spirit gave them utterance.

This may suffice touching the Greek translations of the Old Testament.

Translation out of Hebrew and Greek into Latin

The

Vulgate, translated by Jerome in the 3rd century AD, became the official Latin

Bible. It corrected errors in earlier translations and was based directly on

Hebrew and Greek originals. The Vulgate made the Scriptures accessible to the

Latin-speaking world and became a mainstay of Western Christianity for

centuries.

There were also, within a few hundred years after Christ, many translations into the Latin tongue; for this tongue also was very fit to convey the law and the gospel, because in those times very many countries of the West, yea, of the South, East, and North, spake or understood Latin, being made provinces to the Romans.

But now the Latin translations were too many to be all good, for they were infinite (Latini interpretes nullo modo numerari possunt, saith St. Augustine) [S. Augustin. de doctr. Christ. lib. 2 cap. 11]. Again, they were not out of the Hebrew fountain (we speak of the Latin translations of the Old Testament) but out of the Greek stream; therefore, the Greek being not altogether clear, the Latin derived from it must needs be muddy.

This moved St. Jerome—a most learned Father, and the best linguist without controversy of his age or of any that went before him—to undertake the translating of the Old Testament, out of the very fountains themselves; which he performed with that evidence of great learning, judgment, industry, and faithfulness, that he hath forever bound the church unto him in a debt of special remembrance and thankfulness.

The translating of the Scripture into the vulgar tongues

The

Bible was translated early on into vernacular languages such as Syriac, Gothic

and Slavonic to make God's word accessible to all. These translations spread

Christianity and laid the foundation for future works like the King James

Bible.

Now though the Church were thus furnished with Greek and Latin translations, even before the faith of Christ was generally embraced in the empire (for the learned know that even in St. Jerome's time, the consul of Rome and his wife were both Ethnics, and about the same time the greatest part of the senate also) [S. Hieronym. Marcell. Zosim.]; yet for all that the godly-learned were not content to have the Scriptures in the language which they themselves understood, Greek and Latin (as the good lepers were not content to fare well themselves, but acquainted their neighbors with the store that God had sent, that they also might provide for themselves) [2 Ki. 7:9]; but also for the behoof and edifying of the unlearned, which hungered and thirsted after righteousness, and had souls to be saved as well as they, they provided translations into the vulgar for their countrymen, insomuch that most nations under heaven did shortly after their conversion, hear Christ speaking unto them in their mother tongue, not by the voice of their minister only, but also by the written word translated.

If any doubt hereof, he may be satisfied by examples enough, if enough will serve the turn. First, St. Jerome saith, Multarum gentium linguis Scriptura ante translata, docet falsa esse quae addita sunt, etc.; i.e., "The Scripture being translated before in the languages of many nations, doth show that those things that were added (by Lucian and Hesychius) are false" [S. Hieron. praef. in 4. Evangel.]. So St. Jerome in that place. The same Jerome elsewhere affirmeth that he, the time was, had set forth the translation of the Seventy suae linguae hominibus, i.e., for his countrymen of Dalmatia [S. Hieron. Sophronio.]. Which words not only Erasmus doth understand to purport, that St. Jerome translated the Scripture into the Dalmatian tongue, but also Sixtus Senensis [Six. Sen. lib. 4], and Alphonsus a' Castro [Alphon. a' Castro lib. 1 ca. 23] (that we speak of no more), men not to be excepted against by them of Rome, do ingenuously confess as much.

So St. Chrysostom, that lived in St. Jerome's time, giveth evidence with him: "The doctrine of St. John," saith he, "did not in such sort"—as the philosophers' did—"vanish away; but the Syrians, Egyptians, Indians, Persians, Ethiopians, and infinite other nations, being barbarous people, translated it into their (mother) tongue, and have learned to be (true) philosophers"—he meaneth "Christians" [S. Chrysost. in Johan. cap. hom. 1].

To this may be added Theodoret, as next unto him, both for antiquity and for learning. His words be these: "Every country that is under the sun, is full of these words (of the apostles and prophets) and the Hebrew tongue (he meaneth the Scriptures in the Hebrew tongue) is turned not only into the language of the Grecians, but also of the Romans, and Egyptians, and Persians, and Indians, and Armenians, and Scythians, and Sauromatians, and briefly into all the languages that any nation useth" [Theodor. 5. Therapeut.]. So he.

In like manner, Ulphilas is reported by Paulus Diaconus and Isidore (and before them by Sozomen) to have translated the Scriptures into the Gothic tongue [P. Diacon. lib. 12, Isidor in Chron. Goth, Sozom. lib. 6 cap. 37]. John, bishop of Seville, by Vasseus, to have turned them into Arabic, about the year of our Lord 717 [Vaseus in Chron. Hispan.]; Bede by Cistertiensis, to have turned a great part of them into Saxon; Efnard by Trithemius, to have abridged the French psalter, as Bede had done the Hebrew, about the year 800; King Alfred by the said Cistertiensis, to have turned the psalter into Saxon [Polydor Virg. 5 histor. Anglorum testatur idem de Alvredo nostro]; Methodius by Aventinus (printed at Ingolstadt) to have turned the Scriptures into Slavonian [Aventin. lib. 4.];

Valdo, bishop of Frising, by Beatus Rhenanus, to have caused about that time the gospels to be translated into Dutch rhythm, yet extant in the Library of Corbinian [Circa annum 900. B. Rhenan. rerum German. lib. 2.]; Valdus, by divers to have turned them himself or to have gotten them turned into French, about the year 1160; Charles the Fifth of that name, surnamed the Wise, to have caused them to be turned into French, about 200 years after Valdus's time, of which translation there be many copies yet extant, as witnesseth Beroaldus.

Much about that time, even in our King Richard the Second's days, John Trevisa translated them into English, and many English Bibles in written hand are yet to be seen with divers, translated, as it is very probable, in that age. So the Syrian translation of the New Testament is in most learned men's libraries of Widminstadius's setting forth, and the psalter in Arabic is with many of Augustinus Nebiensis's setting forth. So Postel affirmeth, that in his travel he saw the gospels in the Ethiopian tongue; and Ambrose Thesius allegeth the psalter of the Indians, which he testifieth to have been set forth by Potken in Syrian characters.

So that to have the Scriptures in the mother tongue is not a quaint conceit lately taken up, either by the Lord Cromwell in England, or by the Lord Radevile in Polony [Thuan.], or by the Lord Ungnadius in the emperor's dominion, but hath been thought upon and put in practice of old, even from the first times of the conversion of any nation; no doubt because it was esteemed most profitable to cause faith to grow in men's hearts the sooner, and to make them to be able to say with the words of the Psalms, "As we have heard, so we have seen" [Ps. 48:8].

The unwillingness of our chief adversaries that the Scriptures should be divulged in the mother tongue, etc.

The

Catholic Church long opposed translating the Bible into vernacular languages,

fearing misinterpretation and loss of Church authority. They wanted to keep the

Bible in Latin and demanded permission to read it in native languages. The

translators of the King James Bible criticised this as an attempt to keep

people in spiritual ignorance and darkness.

Now the Church of Rome would seem at length to bear a motherly affection towards her children, and to allow them the Scriptures in their mother tongue. But indeed, it is a gift not deserving to be called a gift—an unprofitable gift (δῶρον ἄδωρον, κοὐκ ὀνήσιμον, Sophocles); they must first get a license in writing before they may use them, and to get that, they must approve themselves to their confessor—that is, to be such as are, if not frozen in the dregs, yet soured with the leaven of their superstition.

Howbeit, it seemed too much to Clement the Eighth that there should be any license granted to have them in the vulgar tongue, and therefore he overruleth and frustrateth the grant of Pius the Fourth. [See the observation (set forth by Clement's authority) upon the fourth rule of Pius the Fourth's making in the Index, lib. prohib., pag. 15. ver. 5.] So much are they afraid of the light of the Scripture (Lucifugae Scripturarum, as Tertullian speaketh [Tertul. de resur. carnis]) that they will not trust the people with it—no, not as it is set forth by their own sworn men; no, not with the license of their own bishops and inquisitors.

Yea, so unwilling are they to communicate the Scriptures to the people's understanding in any sort, that they are not ashamed to confess that we forced them to translate it into English against their wills. This seemeth to argue a bad cause, or a bad conscience, or both.

Sure we are, that it is not he that hath good gold, that is afraid to bring it to the touchstone, but he that hath the counterfeit; neither is it the true man that shunneth the light, but the malefactor, lest his deeds should be reproved [John 3:20]; neither is it the plain-dealing merchant that is unwilling to have the weights, or the meteyard brought in place, but he that useth deceit.

But we will let them alone for this fault, and return to translation.

The speeches and reasons, both of our brethren and of our adversaries, against this work

Protestant brethren questioned the need

for a new translation, while Catholic opponents rejected the work as

threatening the authority of the Church. The translators defended the project

as an improvement to make God's word clearer and more accessible.

Many men's mouths have been open a good while (and yet are not stopped) with speeches about the translation so long in hand, or rather perusals of translations made before, and ask what may be the reason, what the necessity of the employment. Hath the church been deceived, say they, all this while? Hath her sweet bread been mingled with leaven, her silver with dross, her wine with water, her milk with lime? (Lacte gypsum male miscetur, saith St. Irenaeus [S. Iren. 3. lib. cap. 19.].) We hoped that we had been in the right way, that we had had the oracles of God delivered unto us, and that though all the world had cause to be offended and to complain, yet that we had none. Hath the nurse holden out the breast, and nothing but wind in it? Hath the bread been delivered by the Fathers of the Church, and the same proved to be lapidosus, as Seneca speaketh? What is it to handle the word of God deceitfully, if this be not? Thus certain brethren.

Also, the adversaries of Judah and Jerusalem, like Sanballat in Nehemiah, mock, as we hear, both the work and the workmen, saying, "What do these weak Jews, etc.? Will they make the stones whole again out of the heaps of dust which are burnt? Although they build, yet if a fox go up, he shall even break down their stony wall" [Neh. 4:3]. "Was their translation good before? Why do they now mend it? Was it not good? Why then was it obtruded to the people? Yea, why did the Catholics (meaning popish Romanists) always go in jeopardy, for refusing to go to hear it? Nay, if it must be translated into English, Catholics are fittest to do it. They have learning, and they know when a thing is well; they can manum de tabula."

We will answer them both briefly; and the former, being brethren, thus, with St. Jerome: Damnamus veteres? Minime, sed post priorum studia in domo Domini quod possums laboramus [S. Hieron. Apolog. advers. Ruffin.]. That is, "Do we condemn the ancient? In no case, but after the endeavors of them that were before us, we take the best pains we can in the house of God."

As if he said, "Being provoked by the example of the learned men that lived before my time, I have thought it my duty to assay whether my talent in the knowledge of the tongues may be profitable in any measure to God's church, lest I should seem to have labored in them in vain, and lest I should be thought to glory in men (although ancient) above that which was in them." Thus St. Jerome may be thought to speak.

A satisfaction to our brethren

The

translators explained that their work did not reject previous translations but

built on them to improve accuracy and clarity. They emphasised that they were

following the example of their predecessors and working to make the Word of God

even more accessible and understandable to all believers.

And to the same effect say we, that we are so far off from condemning any of their labors that travailed before us in this kind, either in this land or beyond sea, either in King Henry's time or King Edward's (if there were any translation or correction of a translation in his time), or Queen Elizabeth's of ever-renowned memory, that we acknowledge them to have been raised up of God, for the building and furnishing of His church, and that they deserve to be had of us and of posterity in everlasting remembrance. The judgment of Aristotle is worthy and well known: "If Timotheus had not been, we had not had much sweet music; but if Phrynis (Timotheus's master) had not been, we had not had Timotheus" [Arist. 2 Metaphys. cap. 1].

Therefore blessed be they, and most honored be their name, that break the ice and give the onset upon that which helpeth forward the saving of souls. Now, what can be more available thereto than to deliver God's book unto God's people in a tongue which they understand? Since of a hidden treasure and of a fountain that is sealed there is no profit, as Ptolemy Philadelph wrote to the rabbins or masters of the Jews, as witnesseth Epiphanius [S. Epiphan. loco ante citato]; and as St. Augustine saith, "A man had rather be with his dog than with a stranger (whose tongue is strange unto him)" [S. Augustin. *lib. 19. de civit. Dei. cap. 7].

Yet for all that, as nothing is begun and perfected at the same time, and the later thoughts are thought to be the wiser; so, if we, building upon their foundation that went before us, and being helped by their labors, do endeavor to make that better which they left so good, no man, we are sure, hath cause to mislike us; they, we persuade ourselves, if they were alive, would thank us. The vintage of Abiezer that struck the stroke, yet the gleaning of grapes of Ephraim was not to be despised (see Judges 8:2). Joash, the king of Israel, did not satisfy himself till he had smitten the ground three times; and yet he offended the prophet for giving over then [2 Ki. 13:18-19]. Aquila, of whom we spoke before, translated the Bible as carefully and as skillfully as he could; and yet he thought good to go over it again, and then it got the credit with the Jews, to be called kata akribeian, that is, "accurately done," as St. Jerome witnesseth [S. Jerome. in Ezech. cap. 3].

How many books of profane learning have been gone over again and again by the same translators or by others? Of one and the same book of Aristotle's Ethics, there are extant not so few as six or seven several translations. Now if this cost may be bestowed upon the gourd, which affordeth us a little shade, and which today flourisheth but tomorrow is cut down, what may we bestow—nay, what ought we not to bestow—upon the vine, the fruit whereof maketh glad the conscience of man, and the stem whereof abideth forever? And this is the word of God, which we translate. "What is the chaff to the wheat?" saith the Lord [Jer. 23:28]. Tanti vitreum, quanti verum margaritum, saith Tertullian [Tertul. ad Martyr.]—"If a toy of glass be of that reckoning with us, how ought we to value the true pearl?" [Si tanti vilissimum vitrium, quanti pretiosissimum margaritum, Hieron. ad Salvin.].

Therefore let no man's eye be evil, because His Majesty's is good; neither let any be grieved, that we have a prince that seeketh the increase of the spiritual wealth of Israel. (Let Sanballats and Tobiahs do so, which therefore do bear their just reproof.) But let us rather bless God from the ground of our heart, for working this religious care in him, to have the translations of the Bible maturely considered and examined. For by this means it cometh to pass, that whatsoever is sound already (and all is sound for substance, in one or other of our editions, and the worst of ours far better than their authentic vulgar), the same will shine as gold more brightly, being rubbed and polished; also, if anything be halting, or superfluous, or not so agreeable to the original, the same may be corrected, and the truth set in place.

And what can the king command to be done, that will bring him more true honor than this? And wherein could they that have been set at work, approve their duty to the king—yea, their obedience to God and love to His saints—more than by yielding their service, and all that is within them, for the furnishing of the work? But besides all this, they were the principal motives of it, and therefore ought least to quarrel it.

For the very historical truth is, that upon the importunate petitions of the Puritans, at His Majesty's coming to this crown, the conference at Hampton Court having been appointed for hearing their complaints, when by force of reason they were put from all other grounds, they had recourse at the last, to this shift: that they could not with good conscience subscribe to the communion book, since it maintained the Bible as it was there translated, which was (as they said) a most corrupted translation. And although this was judged to be but a very poor and empty shift, yet even hereupon did His Majesty begin to bethink himself of the good that might ensue by a new translation, and presently after gave order for this translation which is now presented unto thee. Thus much to satisfy our scrupulous brethren.

An answer to the imputations of our adversaries

The

translators responded to criticism from Catholic opponents who rejected the

translation as heretical. They defended their work as a faithful improvement on

previous translations, done with care and integrity. They emphasised that the

aim was to spread God's truth, despite opposition from those who wanted to keep

Scripture inaccessible to the people.

Now to the latter we answer that we do not deny—nay, we affirm and avow—that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English, set forth by men of our profession (for we have seen none of theirs of the whole Bible as yet), containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God. As the king's speech, which he uttered in Parliament, being translated into French, Dutch, Italian, and Latin, is still the king's speech, though it be not interpreted by every translator with the like grace, nor peradventure so fitly for phrase, nor so expressly for sense everywhere. For it is confessed that things are to take their denomination of the greater part; and a natural man could say, Verum ubi multa nitent in carmine, non ego paucis offendor maculis, etc. [Horace]—"A man may be counted a virtuous man, though he have made many slips in his life" (else there were none virtuous, for in many things we offend all) [James 3:2]; also a comely man and lovely, though he have some warts upon his hand—yea, not only freckles upon his face, but also scars.

No cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current, notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it. For whatever was perfect under the sun, where apostles or apostolic men—that is, men endued with an extraordinary measure of God's spirit, and privileged with the privilege of infallibility—had not their hand? The Romanists therefore, in refusing to hear, and daring to burn the word translated, did no less than despite the Spirit of grace, from whom originally it proceeded, and whose sense and meaning, as well as man's weakness would enable, it did express.

Judge by an example or two. Plutarch writeth that after that Rome had been burnt by the Gauls, they fell soon to build it again; but doing it in haste, they did not cast the streets, nor proportion the houses in such comely fashion, as had been most sightly and convenient [Plutarch in Camillo.]. Was Catiline therefore an honest man, or a good patriot, that sought to bring it to a combustion? or Nero a good prince, that did indeed set it on fire? So by the story of Ezra and the prophecy of Haggai it may be gathered, that the temple built by Zerubbabel after the return from Babylon was by no means to be compared to the former built by Solomon (for they that remembered the former wept when they considered the latter) [Ezr. 3:12]; notwithstanding, might this latter either have been abhorred and forsaken by the Jews, or profaned by the Greeks?

The like we are to think of translations. The translation of the Seventy dissenteth from the original in many places; neither doth it come near it, for perspicuity, gravity, majesty; yet which of the apostles did condemn it? Condemn it? Nay, they used it (as it is apparent, and as St. Jerome and most learned men do confess), which they would not have done, nor by their example of using it so grace and commend it to the church, if it had been unworthy the appellation and name of the word of God.

And whereas they urge for their second defense of their vilifying and abusing of the English Bibles, or some pieces thereof which they meet with, for that "heretics," forsooth, were the authors of the translations ("heretics" they call us by the same right that they call themselves "Catholics," both being wrong), we marvel what divinity taught them so. We are sure Tertullian was of another mind: Ex personis probamus fidem, an ex fide personas? [Tertul. de praescript. contra haereses.]—"Do we try men's faith by their persons? We should try their persons by their faith."

Also St. Augustine was of another mind, for he, lighting upon certain rules made by Tychonius, a Donatist, for the better understanding of the word, was not ashamed to make use of them—yea, to insert them into his own book, with giving commendation to them so far forth as they were worthy to be commended, as is to be seen in St. Augustine's third book De doctrina Christiana [S. August. 3. de doct. Christ. cap. 30.].

To be short, Origen and the whole church of God for certain hundred years were of another mind, for they were so far from treading under foot (much more from burning) the translation of Aquila, a proselyte (that is, one that had turned Jew)—of Symmachus, and Theodotion, both Ebionites (that is, most vile heretics)—that they joined them together with the Hebrew original, and the translation of the Seventy (as hath been before signified out of Epiphanius) and set them forth openly to be considered of and perused by all.

But we weary the unlearned, who need not know so much, and trouble the learned, who know it already.

Yet before we end, we must answer a third cavil and objection of theirs against us, for altering and amending our translations so often; wherein truly they deal hardly and strangely with us. For to whom ever was it imputed as a fault (by such as were wise) to go over that which he had done, and to amend it where he saw cause? St. Augustine was not afraid to exhort St. Jerome to a palinodia or recantation, and doth even glory that he seeth his infirmities [S. Aug. Epist. 9; S. Aug. lib. Retractat.; Video interdum vitia mea, S. Aug. Epist. 8.]. If we be sons of the truth, we must consider what it speaketh, and trample upon our own credit, yea, and upon other men's too, if either be any way a hindrance to it.

This to the cause. Then to the persons we say, that of all men they ought to be most silent in this case. For what varieties have they, and what alterations have they made, not only of their service books, portasses, and breviaries, but also of their Latin translation? The service book supposed to be made by St. Ambrose (Officium Ambrosianum) was a great while in special use and request, but Pope Hadrian, calling a council with the aid of Charles the Emperor, abolished it—yea, burned it—and commanded the service book of St. Gregory universally to be used [Durand. lib. 5. cap. 2.]. Well, Officium Gregorianum gets by this means to be in credit, but doth it continue without change or altering? No, the very Roman service was of two fashions, the "new" fashion and the "old"—the one used in one church, the other in another—as is to be seen in Pamelius, a Romanist, his preface before Micrologus.

The same Pamelius reporteth out of Radulphus de Rivo that about the year of our Lord 1277, Pope Nicolas the Third removed out of the churches of Rome the more ancient books (of service), and brought into use the missals of the Friars Minorites, and commanded them to be observed there; insomuch that about a hundred years after, when the above-named Radulphus happened to be at Rome, he found all the books to be new (of the new stamp). Neither were there these choppings and changings in the more ancient times only, but also of late: Pius Quintus himself confesseth, that every bishopric almost had a peculiar kind of service, most unlike to that which others had; which moved him to abolish all other breviaries, though never so ancient, and privileged and published by bishops in their dioceses, and to establish and ratify that only which was of his own setting forth, in the year 1568.*

Now when the father of their church, who gladly would heal the sore of the daughter of his people softly and slightly, and make the best of it, findeth so great fault with them for their odds and jarring, we hope the children have no great cause to vaunt of their uniformity. But the difference that appeareth between our translations, and our often correcting of them, is the thing that we are specially charged with. Let us see therefore whether they themselves be without fault this way (if it be to be counted a fault, to correct), and whether they be fit men to throw stones at us. O tandem major parcas insane minori—"They that are less sound themselves, ought not to object infirmities to others" [Horat.].

If we should tell them that Valla, Stapulensis, Erasmus, and Vives found fault with their vulgar translation, and consequently wished the same to be mended, or a new one to be made, they would answer peradventure, that we produced their enemies for witnesses against them; albeit, they were in no other sort enemies than as St. Paul was to the Galatians, for telling them the truth [Gal. 4:16]; and it were to be wished that they had dared to tell it them plainer and oftener. But what will they say to this, that Pope Leo the Tenth allowed Erasmus' translation of the New Testament, so much different from the vulgar, by his apostolic letter and bull; that the same Leo exhorted Pagnin to translate the whole Bible, and bore whatsoever charges were necessary for the work [Sixtus Senens.]? Surely, as the apostle reasoneth to the Hebrews, that "if the former law and testament had been sufficient, there had been no need of the latter" [Heb. 7:11, 8:7], so we may say, that if the old vulgar had been at all points allowable, to small purpose had labour and charges been undergone about framing of a new.

If they say, it was one pope's private opinion, and that he consulted only himself, then we are able to go further with them, and to aver that more of their chief men of all sorts, even their own Trent champions Paiva and Vega, and their own inquisitors, Hieronymus ab Oleastro, and their own Bishop Isidorus Clarius, and their own Cardinal Thomas a Vio Caietan, do either make new translations themselves, or follow new ones of other men's making, or note the vulgar interpreter for halting; none of them fear to dissent from him, nor yet to except against him. And call they this an uniform tenor of text and judgment about the text, so many of their worthies disclaiming the now received conceit?

Nay, we will yet come nearer the quick: doth not their Paris edition differ from the Louvain, and Hentenius his from them both, and yet all of them allowed by authority? Nay, doth not Sixtus Quintus confess, that certain Catholics (he meaneth certain of his own side) were in such a humour of translating the Scriptures into Latin, that Satan taking occasion by them, though they thought of no such matter, did strive what he could, out of so uncertain and manifold a variety of translations, so to mingle all things that nothing might seem to be left certain and firm in them, etc. [Sixtus 5. praefat. fixa Bibliis.]? Nay, further, did not the same Sixtus ordain by an inviolable decree, and that with the counsel and consent of his cardinals, that the Latin edition of the Old and New Testament, which the Council of Trent would have to be authentic, is the same without controversy which he then set forth, being diligently corrected and printed in the printing house of Vatican? Thus Sixtus in his preface before his Bible.

And yet Clement the Eighth, his immediate successor, published another edition of the Bible, containing in it infinite differences from that of Sixtus (and many of them weighty and material), and yet this must be authentic by all means. What is to have the faith of our glorious Lord Jesus Christ with "yea and nay," if this be not? Again, what is sweet harmony and consent, if this be? Therefore, as Demaratus of Corinth advised a great king, before he talked of the dissensions among the Grecians, to compose his domestic broils (for at that time his queen and his son and heir were at deadly feud with him), so all the while that our adversaries do make so many and so various editions themselves, and do jar so much about the worth and authority of them, they can with no show of equity challenge us for changing and correcting.

The purpose of the translators with their number, furniture, care, etc.

The

translators' goal was to create the most accurate and clear Bible translation

possible, based on the original Hebrew and Greek texts. The team consisted of

many learned men, chosen for their knowledge and experience. They worked with

great care, using available resources, including previous translations and

commentaries, to ensure quality and fidelity to the originals. The work was

done prayerfully and with a deep sense of responsibility before God and the

Church.

But it is high time to leave them, and to show in brief what we proposed to ourselves, and what course we held in this our perusal and survey of the Bible. Truly, good Christian reader, we never thought from the beginning that we should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one (for then the imputation of Sixtus had been true in some sort, that our people had been fed with gall of dragons instead of wine, with whey instead of milk); but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one, not justly to be excepted against. That hath been our endeavor, that our mark.

To that purpose, there were many chosen that were greater in other men's eyes than in their own, and that sought the truth rather than their own praise. Again, they came, or were thought to come, to the work, not exercendi causa (as one saith) but exercitati, that is, "learned, not to learn." For the chief overseer and ἐργοδιώκτης under his Majesty, to whom not only we, but also our whole church was much bound, knew by his wisdom--which thing also Nazianzen taught so long ago--that it is a preposterous order to teach first and to learn after, yea that to ἐν πίθῳ κεραμίαν μανθάνειν, "to learn and practice together," is neither commendable for the workman, nor safe for the work [Nazianzen, Εἰς Ῥην. ἐπισκ. παροῦσ., Idem in Apologet.].

Therefore such were thought upon as could say modestly with St. Jerome, Et Hebraeum sermonem ex parte didicimus, et in Latino pene ab ipsis incunabulis, etc., detriti sumus--"Both we have learned the Hebrew tongue in part, and in the Latin we have been exercised almost from our very cradle." (St. Jerome maketh no mention of the Greek tongue, wherein yet he did excel, because he translated not the Old Testament out of Greek, but out of Hebrew.)

And in what sort did these assemble? In the trust of their own knowledge, or of their sharpness of wit, or deepness of judgment, as it were in an arm of flesh? At no hand. They trusted in him that hath the key of David, opening and no man shutting; they prayed to the Lord, the Father of our Lord, to the effect that St. Augustine did: "O let thy Scriptures be my pure delight; let me not be deceived in them, neither let me deceive by them" [S. Aug. lib. 11. Confess. cap. 2.]. In this confidence and with this devotion did they assemble together; not too many, lest one should trouble another, and yet many, lest many things haply might escape them.

If you ask what they had before them, truly it was the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, the Greek of the New. These are the two golden pipes, or rather conduits, wherethrough the olive branches empty themselves into the gold. St. Augustine calleth them precedent, or original tongues [S. August. 3. de doctr. c. 3. etc.]; St. Jerome, fountains [S. Hieron. ad Suniam et Fretel.]. The same St. Jerome affirmeth, and Gratian hath not spared to put it into his decree, that "as the credit of the old books (he meaneth of the Old Testament) is to be tried by the Hebrew volumes, so of the New by the Greek tongue (he meaneth by the original Greek) [S. Hieron. ad Lucinium, Dist. 9 ut veterum.].

If truth be tried by these tongues, then whence should a translation be made, but out of them? These tongues therefore--the Scriptures, we say, in those tongues--we set before us to translate, being the tongues wherein God was pleased to speak to His church by His prophets and apostles. Neither did we run over the work with that posting haste that the Septuagint did, if that be true which is reported of them, that they finished it in seventy-two days [Joseph. Antiq. lib. 12.]; neither were we barred or hindered from going over it again, having once done it, like St. Jerome--if that be true which himself reporteth, that he could no sooner write anything but presently it was caught from him and published, and he could not have leave to mend it [S. Hieron. ad Pammac. pro libr. advers. Iovinian.].

Neither, to be short, were we the first that fell in hand with translating the Scripture into English, and consequently destitute of former helps, as it is written of Origen, that he was the first (πρωτοπείροι) in a manner that put his hand to write commentaries upon the Scriptures, and therefore no marvel if he overshot himself many times. None of these things; the work hath not been huddled up in seventy-two days, but hath cost the workmen, as light as it seemeth, the pains of twice seven times seventy-two days and more.

Matters of such weight and consequence are to be speeded with maturity, for in a business of moment a man feareth not the blame of convenient slackness (φιλεῖ γὰρ ὀκνεῖν πράγματ' ἀνὴρ πράσσων μεγά, Sophoc. in Elect.). Neither did we think much to consult the translators or commentators, Chaldee, Hebrew, Syrian, Greek, or Latin--no, nor the Spanish, French, Italian, or Dutch. Neither did we disdain to revise that which we had done, and to bring back to the anvil that which we had hammered; but having and using as great helps as were needful, and fearing no reproach for slowness, nor coveting praise for expedition, we have at length, through the good hand of the Lord upon us, brought the work to that pass that you see.

Reasons moving us to set diversity of senses in the margin, where there is great probability for each

The

translators included alternative interpretations in the margin where the text

could be understood in different ways. This was done to help the reader

understand difficult passages and avoid presenting a single interpretation as

absolute. They believed that this approach encouraged accuracy, humility and

deeper study of Scripture.

Some peradventure would have no variety of senses to be set in the margin, lest the authority of the Scriptures for deciding of controversies by that show of uncertainty should somewhat be shaken. But we hold their judgment not to be so sound in this point. For though "whatsoever things are necessary are manifest," as St. Chrysostom saith (πάντα τὰ ἀναγκαῖα δῆλα, S. Chrysost. in 2 Thess. cap. 2.), and as St. Augustine, "In those things that are plainly set down in the Scriptures, all such matters are found that concern faith, hope, and charity" (S. Aug. 2. De doctr. Christ. cap. 9.); yet for all that it cannot be dissembled, that partly to exercise and whet our wits, partly to wean the curious from the loathing of them for their everywhere plainness, partly also to stir up our devotion to crave the assistance of God's Spirit by prayer, and lastly, that we might be forward to seek aid of our brethren by conference, and never scorn those that be not in all respects so complete as they should be, being to seek in many things ourselves, it hath pleased God in His divine providence, here and there to scatter words and sentences of that difficulty and doubtfulness, not in doctrinal points that concern salvation (for in such it hath been vouched that the Scriptures are plain), but in matters of less moment, that fearfulness would better beseem us than confidence, and if we will resolve upon modesty with St. Augustine (though not in this same case altogether, yet upon the same ground), Melius est dubitare de occultis, quam litigare de incertis (S. Aug. lib. 8. De Genes. ad liter. cap. 5.)--"it is better to make doubt of those things which are secret, than to strive about those things that are uncertain."

There be many words in the Scriptures which be never found there but once (having neither brother nor neighbor (ἅπαξ λεγόμενα), as the Hebrews speak), so that we cannot be holpen by conference of places. Again, there be many rare names of certain birds, beasts, and precious stones, etc., concerning which the Hebrews themselves are so divided among themselves for judgment, that they may seem to have defined this or that rather because they would say something than because they were sure of that which they said, as St. Jerome somewhere saith of the Septuagint.

Now in such a case, doth not a margin do well to admonish the reader to seek further, and not to conclude or dogmatize upon this or that peremptorily? For as it is a fault of incredulity to doubt of those things that are evident, so to determine of such things as the Spirit of God hath left (even in the judgment of the judicious) questionable, can be no less than presumption. Therefore as St. Augustine saith, that variety of translations is profitable for the finding out of the sense of the Scriptures (S. Aug. 2. De doctr. Christ. cap. 14.), so diversity of signification and sense in the margin, where the text is not so clear, must needs do good--yea, is necessary, as we are persuaded.

We know that Sixtus Quintus expressly forbiddeth that any variety of readings of their vulgar edition should be put in the margin (Sixtus 5. praef. Bibliae.)--which though it be not altogether the same thing to that we have in hand, yet it looketh that way--, but we think he hath not all of his own side his favorers for this conceit. They that are wise had rather have their judgments at liberty in differences of readings, than to be captivated to one, when it may be the other.

If they were sure that their high priest had all laws shut up in his breast, as Paul the Second bragged [Plat. in Paulo secundo.], and that he were as free from error by special privilege as the dictators of Rome were made by law inviolable, it were another matter; then his word were an oracle, his opinion a decision. But the eyes of the world are now open, God be thanked, and have been a great while. (ὁμοιοπαθὴς τρόπος γὰρ οἱ χρός ἐστι.) They find that he is subject to the same affections and infirmities that others be, that his skin is penetrable; and therefore so much as he proveth, not as much as he claimeth, they grant and embrace.

Reasons inducing us not to stand curiously upon an identity of phrasing

The

translators chose to use different expressions for the same concept to reflect

the richness of the language and avoid rigidity. They believed that variation

in wording makes the text more lively and accessible without losing its

meaning. They strived for freedom of language rather than the constraint of

strict uniformity.

Another thing we think good to admonish thee of, gentle reader: that we have not tied ourselves to an uniformity of phrasing, or to an identity of words, as some peradventure would wish that we had done, because they observe that some learned men somewhere have been as exact as they could that way. Truly, that we might not vary from the sense of that which we had translated before, if the word signified the same thing in both places (for there be some words that be not of the same sense everywhere (πολύσημα)), we were especially careful, and made a conscience according to our duty.

But that we should express the same notion in the same particular word, as for example, if we translate the Hebrew or Greek word once by purpose, never to call it intent; if one where journeying, never travelling; if one where think, never suppose; if one where pain, never ache; if one where joy, never gladness, etc.—thus, to mince the matter, we thought to savor more of curiosity than wisdom, and that rather it would breed scorn in the atheist than bring profit to the godly reader. For is the kingdom of God become words or syllables? Why should we be in bondage to them if we may be free, use one precisely when we may use another no less fit, as commodiously?

A godly Father in the Primitive time showed himself greatly moved, that one of newfangleness called κράββατον, "σκίμπους" ("a bed"; Niceph. Calist. lib. 8. cap. 42.), though the difference be little or none; and another reporteth that he was much abused for turning κύκιον (to which reading the people had been used) into ἕδρα [S. Hieron. in 4. Ionae. See S. Aug. epist. 10.].

Now if this happen in better times, and upon so small occasions, we might justly fear hard censure, if generally we should make verbal and unnecessary changings. We might also be charged (by scoffers) with some unequal dealing towards a great number of good English words. For as it is written of a certain great philosopher, that he should say, that those logs were happy that were made images to be worshipped, for their fellows, as good as they, lay for blocks behind the fire; so if we should say, as it were, unto certain words, "Stand up higher; have a place in the Bible always," and to others of like quality, "Get ye hence; be banished forever," we might be taxed peradventure with St. James his words, namely, "To be partial in ourselves, and judges of evil thoughts."

Add hereunto, that niceness in words was always counted the next step to trifling, and so was to be curious about names, too; also, that we cannot follow a better pattern for elocution than God Himself; therefore, He using divers words, in His holy writ, and indifferently for one thing in nature (λεπτολογία; ἀδολεσχία; το σπουδάζειν ἐπί ὀνόμασιν; see Euseb. προπαρασκευή. λίβ. 12. ex Platon.), we, if we will not be superstitious, may use the same liberty in our English versions out of Hebrew and Greek, for that copy or store that He hath given us.

Lastly, we have on the one side avoided the scrupulosity of the Puritans, who leave the old ecclesiastical words and betake them to other, as when they put washing for baptism, and congregation instead of church; as also on the other side we have shunned the obscurity of the Papists, in their azimes, tunic, rational, holocausts, praepuce, pasche, and a number of such like, whereof their late translation is full—and that of purpose to darken the sense, that since they must needs translate the Bible, yet by the language thereof, it may be kept from being understood.*

But we desire that the Scripture may speak like itself, as in the language of Canaan, that it may be understood even of the very vulgar.

Many other things we might give thee warning of, gentle reader, if we had not exceeded the measure of a preface already. It remaineth that we commend thee to God, and to the Spirit of His grace, which is able to build further than we can ask or think. He removeth the scales from our eyes, the veil from our hearts, opening our wits that we may understand His word, enlarging our hearts; yea, correcting our affections, that we may love it to the end.

Ye are brought unto fountains of living water which ye digged not; do not cast earth into them with the Philistines [Gen. 26:15], neither prefer broken pits before them with the wicked Jews [Jer. 2:13]. Others have laboured, and you may enter into their labours. O receive not so great things in vain, O despise not so great salvation! Be not like swine to tread under foot so precious things, neither yet like dogs to tear and abuse holy things. Say not to our Saviour with the Gergesites, "Depart out of our coasts" [Matt. 8:34]; neither yet with Esau sell your birthright for a mess of pottage [Heb. 12:16]. If light be come into the world, love not darkness more than light; if food, if clothing be offered, go not naked, starve not yourselves.

Remember the advice of Nazianzene, "It is a grievous thing (or dangerous) to neglect a great fair, and to seek to make markets afterwards" [Ναζιανζ. περὶ ἀγ. βαπτ. δεινὸν πανήγυριν παρελθεῖν καὶ τὴν ἡνίκαυτα πραγματείαν ἐπιζητεῖν]; also the encouragement of St. Chrysostom, "It is altogether impossible, that he that is sober (and watchful) should at any time be neglected" [S. Chrysost. in epist. ad Rom. cap. 14. orat. 26. in ἠθικ. ἀμηχάνων σφόδρα ἀμηχάνων]; lastly, the admonition and menacing of St. Augustine, "They that despise God's will inviting them, shall feel God's will taking vengeance of them" [S. August. ad artic. sibi falso object. Artic. 16.].

It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God [Heb. 10:31]; but a blessed thing it is, and will bring us to everlasting blessedness in the end, when God speaketh unto us, to hearken; when He setteth His word before us, to read it; when He stretcheth out His hand and calleth, to answer, "Here am I! here we are to do thy will, O God."

The Lord work a care and conscience in us to know Him and serve Him, that we may be acknowledged of Him at the appearing of our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom, with the Holy Ghost, be all praise and thanksgiving. Amen.

(The summary under the headings and the Notes are added by the Bible Library and are not part of the KJV 1611 Preface.)

KJV

Miles Smith: Author of the ‘Preface to Readers’ 1611

Miles Smith (1554-1624) was an English bishop, theologian and one of the prominent translators of the King James Bible. He played a central role in the translation process and is best known as the author of the famous ‘Translators to the Reader’ in the 1611 edition.

Smith had a deep knowledge of Hebrew, Greek and Latin, and served on the sixth translation committee, which reviewed and compiled the final version of the text. His foreword reflects his dedication to both the Bible and the translation project. The text is full of eloquence and wisdom, describing the aims, methods and challenges of the translators.

As Bishop of Gloucester from 1612 until his death on 20 October 1624, Smith also contributed to theological and academic life in England. His work and his prefaces have continued to inspire readers and scholars for centuries.